A few days ago we passed a poster on a door that said: “Remember why you became a scientist?” It was a poster promoting outreach activities, such as promoting STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) in primary schools. However, it had a slightly different effect on us. A simultaneous groan was uttered. You must know that this happened in the middle of the week, a quite stressful week for most of us. I also had a hard time remembering. PhD’s tend to go in ups and downs, a fact that is sometimes cleverly used for a whole range of webcomics. And at that moment, even though I’m only 6 months – no wait, 7 months – into my PhD so I can hardly complain, it was a bit of a down. So running into a poster asking if I remember why I wanted to be a scientist caused me to slip into a tiny existential crisis.

Luckily it didn’t take to much remembering.

In the good old days of sending around questionnaires (“How well do you know me?“) by email, a friend filled in the following:

Q: What will I be when I grow up?

A: an inventor

It all fit. When we were kids, that friend and I had made plans to build a “test-car”, where we could interchange the engine to test different alternative fuels, not-so-loosely based on the grasmobile. It never got past the plans, but nevertheless, we had the ambition to better the world and help the environment. We wrote poems about time travel. My personal heroes were not movie stars or superheroes, but the quirky old professors in the comics I read, like Professor Barabas, Professor Gobelijn or even Professor Zonnebloem (Professor Calculus). All bonkers (especially the latter), but amazing geniuses. I played with a microscope, collecting leaves and dirt to look at. I had plans to solve global warming and cure cancer.

I became a bit more realistic when I got older, but still, I got into engineering and research. I still want to discover the world, make an impact and make the world an ever so slightly better place.

Beside that, I simply like science. I find pleasure talking about it with friends, reading about new new findings, in short, simply geeking out. Science is awesome. We scientists just loose sight of that sometimes.

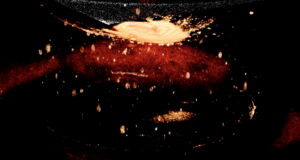

And if I have a hard time remembering, I have results to remind us. Even if things don’t turn out exactly the way I predicted or hoped, interesting thins happen: A 3D OCT* scan that looks like a galaxy;

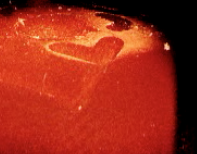

or a result just simply asking me to be its valentine…

So there is still hope for me!

* Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) uses the interference patterns of backscattered light to form an image, or in other words: as light travels through a sample, it is scattered back differentially by different objects in the samples. By looking at the light coming back and comparing it to your initial light beam, you can deduct structural information of your sample. The “stars” in the image, the bright dots, are hopefully spheroids of cells. The brightest spot in the middle is strong reflection from the liquid surface (because it’s not flat). Another way to think about OCT is “Ultrasound with light.”