I recently watched the documentary The Inventor: Out For Blood In Silicon Valley. And boy, do I have some thoughts.

Theranos: Therapy meets Diagnostics

The documentary depicts on the rise and fall of Elizabeth Holmes, founder, and CEO of the biotech company Theranos. Briefly, here is what happened:

At the age of 19, she dropped out of university and founded a company on the idea of creating a diagnostic blood test that could test for over 200 different markers using only a few drops of blood, that could be taken with a prick of a fingertip. You know, the kind they use to measure your hemoglobin when you donate blood.

The aspiration was to give the power of therapeutics and diagnostics (Theranos = THERApy + diagNOSis) to the individual, making tests significantly cheaper, less scary (no needles!), and easier for the consumer to interpret. And earlier disease detection means earlier treatment and better survival!

She founded the company in 2003 and raised over $700 million from venture capitalists and private investors in the next decade. By 2013, the company was valued at $10 billion. In 2015, the validity of technology was questioned and Holmes, and Theranos with her, fell. Three years later, in 2018, Holmes and Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani, former Theranos Chief Operating Officer and President, were both charged with fraud and conspiracy. The Theranos saga had ended.

You can read more about Theranos and Holmes’ rise and fall on the interwebs, or watch one of the several documentaries made about the story. Rather than give you the details of Theranos, I’d like to talk more about my thoughts after watching this documentary – as a bioengineer who in 2013 was studying nanotechnology, working on a project involving “theranostics” (THERApeutics + diagNOSTICS, sound familiar?) and has more recently worked in a startup environment.

Nanotechnology and Microfluidics

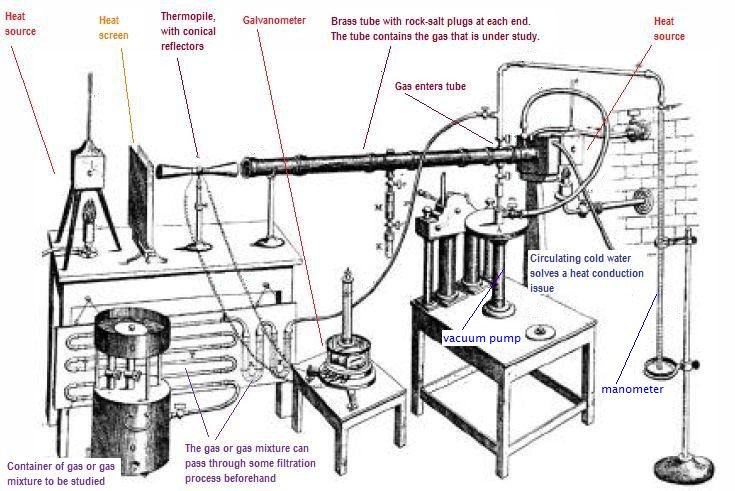

From 2011 and 2013, right when Theranos was about to hit its peak, I was studying nanotechnology. The technology Theranos’ system was based on (or so they claimed) was exactly the same type of stuff I was learning about. To be able to do diagnostics on small samples, the liquid handling and detection techniques need to be scaled down, using principles of microfluidics (I was also learning about that).

I distinctly remember giving a presentation about microfluidic chips that could process blood in a way to split out the different components, i.e. centrifugation at a teeny tiny scale.

From what I remember, at that time most of this technology was still in the research phase: individual university research groups and some research institutions coming up with new approaches to handle small blood samples for diagnostic testing. Were they able to do 200s of tests on the samples? Not that I know. Was any of the technology commercially viable at the time? Not that I know. But then again, I was only studying this stuff and in no way an expert.

More importantly, I don’t remember hearing about Theranos. It clearly had not made enough of a buzz, scientifically, to reach across the pond.

When I was watching the documentary, it talked a little bit about the technology and my reaction was: “That won’t work. You can try to scale down one or two of these tests to work with small samples OR you can try to do a lot more tests with the same amount of sample. But not both at the same time, that’s just sounds idealistic!”

Clearly, it didn’t. (Obviously, otherwise, there would not have been as many articles written about this, or documentaries made.)

Why we still love a genius

Part of the reason people bought into the Theranos story, is because it was enticing. This young women, who wore turtlenecks (Steve Jobs much?) and felt like she had to lower her voice to be taken more seriously, Silicon Valley just loved her. Part of being part of startup culture is being good at selling a story – whether it’s factual or not, realistic or not, is beside the point.

Another reason Theranos was successful at first and able to raise so much money was that Holmes was extremely well connected. She was charismatic. She was able to surround herself with big names, from the world of investment, military, law and even politics.

Here’s the thing, I get it. Seeing images of this young woman, who clearly is motivated by making the world a better place, who clearly made an effort to hire an inclusive and diverse workforce, who was able to found a company at such a young age, after dropping out of college no less, I would have admired her too! Making it “big” as a woman in the male-dominated tech world is not an easy feat and she seemed to have made it happen (at the time).

But here’s another thought: why do we so want to love the story of a “genius”? We love hearing about wunderkinder and how they become the youngest to do this or the first to do that. Is it because somehow we think that we too can be a genius. That we can have our own great amazing story. But most of us won’t (and that’s okay).

Maybe we should stop glorifying individuals in science, research, and tech, because especially nowadays, science doesn’t happen in isolation. Progress happens in small steps with massive groups of people collaborating to make it happen.

(Yet, we still have Nobel Prizes and love celebrating greatness.)

Why we love to see someone fall

We love to admire an individual making it happen against all odds, working so hard so they can make it, despite the system working against them. But similarly, we love seeing someone on the top fall. Perhaps we like seeing them fail so we can feel better about ourselves not “succeeding” as they did. And then didn’t

What I disliked about “The Inventor,” is that it made it seem like it was all Holmes’ fault. They spoke to some of the men that invested in her company, that believed in her, and they all tried to shift the blame to her, like she had “seduced” them into supporting her too idealistic cause.

Holmes’ surrounded herself with Yes-men. Surround yourself with people who keep telling you that you’re great, and you will start thinking you’re great. Just like being told over and over again that your not good enough for something will get to your head.

The documentary, with overly dramatic animations of blood getting into a microcentrifuge system and a dice rolling, makes Holmes look evil. And the person around her, who enabled her, as victims of her charm. And the same type of men then went ahead to explain how she failed.

Of course, Holmes’ did play a big part in this story, but she’s not the only one to blame. It’s the system that gives people the privilege of better networks and connections to succeed without really having to try. It’s the culture of Silicon Valley that celebrates taking risks when they are completely ridiculous to take. It’s the startup mentality of “Fake it till you make it,” forgetting that quite often they won’t actually make it. It’s all of us, that love hearing about wunderkinder and geniuses and celebrate the individual instead of the collective for their achievements.

The end

How to I end this word vomit about how perhaps glorification of geniuses is perhaps not the healthiest thing?

Well, people do have good ideas. And sometimes the high-risk, high-reward world of tech and startups is the way to make these good ideas happen. And sometimes those ideas fail and we should just admit to ourselves why we enjoy watching that happen.

To quote the YouTuber MedLife Crisis (paraphrased): We shouldn’t hype medicine. Thank you vfor coming to my MedTalk.