Giving a talk is hard. Giving a talk to the “general public,”* is possibly even harder. What if people don’t care about what you’re talking about? What if you’re not able to explain it in a clear way, without “dumbing it down”? There are many pitfalls to giving a public talk, and from giving and going to quite a few myself, I have a few ideas on how to make sure you nail your next talk!

A mistake I’ve seen quite a lot is diving straight into the data. But that will immediately lose anyone in the audience who is not an expert in [insert topic of talk here]. Here’s an example outline for a [fictional] talk about research on a sciency thing:

1. Set the stage

Tell the audience why they should care. Maybe your research is on ice shelf stability and there was something recently in the news about a city-sized chunk of ice breaking off an Antarctic ice shelf. Lucky you! (not so lucky for the ice shelf though). Use that powerful image as your first slide!

Or maybe what you’re talking to contributes to the rising sea level? Great for you! (not so great for the Netherlands though). Use that striking image of cities that will disappear as your other introduction slide.

Or, if you’re like me, your research is (was) about the Physics of Cancer. I like to start talks pointing out that “physics” and “cancer” are not necessarily two concepts that we think about in the same context.

Whatever you’re research is about, there is a reason to care and a very illustrative image to accompany your impassioned exposé of why we should all be caring. You’re learning more about how cells work which can lead to better disease treatment. You’re satisfying our human need to keep on exploring by making better rockets to send into space. You’re leading to a better understanding of how humans interact with each other which will help us all be better to each other.

I don’t know, I’m just spitballing, but your research is important and we should care. And there is most definitely a meme, powerful image, or powerful gif available that shows us why.*** Because, let’s face it, we all like pictures more than words, no?

2. What do we know?

Time to show some numbers. Maybe there are some prediction models and the observations made in the last decades are increasingly matching those (scary) predictions. If you’re giving that talk about sea-level rise, show the climate temperature rise graph. If your talk is on a new and tinier microchip, Moore’s Law is your thing to show. If your talk is on cancer, you can give some numbers on incident rates, or how earlier detection can lead to earlier and better treatment.

In my case, my second slide is an overview of what cancer actually is, followed by an outline of what my talk is about: how understanding the changing mechanical properties of cells and tissue can help us better understand how cancer works, improve diagnostics, and come up with better ways to detect cancer.

In short, set your research into a more general perspective. What is the current view on this subject, and where are the giant gaps in the knowledge. Because that’s where you come in!

Tip: if you ever start a slide with “there’s probably too much data on this slide…”, just don’t. Break it up into multiple slides. Only show the data that matters for what you’re saying. Anything but saying there’s too much data.

3. Time to shine!

This is where you can plug in your stuff. What is new about it? What problem is it solving? What does this new shiny data show?

Some tips to help:

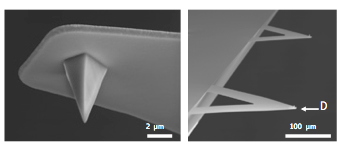

Show the process of your research and tell a story. People really like hearing stories about science is done. Maybe there’s an anecdote about how you were messing around with scotch tape and suddenly discovered graphene. Or about how you were able to hitch a ride to the field study and made an unusual friend. Or how the first time you set up the Atomic Force Microscope, which uses a tiny micro-probe, you broke the tip right when the professor walked into the lab.

Also, don’t “half” introduce a complicated concept. If you need to explain a complicated technique to explain your results, go ahead. But don’t half-mention them and leave the audience wondering what that word (or abbreviation) was all about. Did you know that AFM can refer to Atomic Force Microscopy, Acute Flaccid Myelitis, or the American Film Market?

4. Conclusions

End your talk by looping it back to the first point. You told us why we should care about the subject, now tell us what your new findings mean for that subject. Add some future perspectives. Add another meme. Add an inspirational quote. Leave time for questions. Or if you’re me, you might take out a ukulele and sing a song.

A final tip, make sure you plan your talk in advance! There is nothing more frustrating than seeing someone rush through their slides because they didn’t do a run through.

If you are in research and early in your career, such as a PhD student or a Post-Doc, you might have the chance to take some science communication training through your institution. I would highly recommend it! There are plenty of resources online as well!

Final thought, I secretly believe that scientists at all levels should take get training and practice about giving engaging presentations, to whichever audience, and learn how to make sure your audience doesn’t get put to sleep.

Good luck! You got this!

* “General public” is the worst blanket description of an audience. Let’s just say that the people who might come to a public lecture are not experts in whatever you are talking about but do have an interest in it (or they wouldn’t be there).

** I’m kidding. I’m technically from New Jersey.

*** Yes, I know I used a wordcloud as an example.