Last Friday, a few of my colleagues – and by that I mean “a few of those crazy nerdy people who are in the same PhD programme as me and have become my friends over time partially because we’re just stuck in the same boat together but mostly because they are absolutely amazing” -, including myself, have started a course on “Astrobiology and the Search of Life”.

None of us actually works in that field (I was amazed that astrobiology is a field, how cool is that?), and we might be in it for easy credit, but it just seemed interesting. Okay, perhaps the first class was very introductory and didn’t have many take-home messages. I was suffering an episode of my SISS (Sedentarily Induced Somnia Syndrome; I refer you to a post that I will write sometime in the future on make-believe acronyms for make-believe psychological conditions) so I *might* have been dosing off a bit, but I do remember a few key points the lecturer made.

Astrobiology is about answering perhaps one of the most important questions: Are we alone in the Universe? It is however, not about “finding aliens”, it’s about studying the conditions required for life (luckily we happen to live on an excellent repository of information on life) and looking for evidence of potential life, in the past or still to come, out there in space. We’re lucky to live in an age where it’s more than just speculation, we can empirically set out and look for this evidence, or at least to a certain extent.

Actually, I’ve had some notes floating around in my draft scribbles about this very topic. It seems a good time as any to group them together into a well-researched, well-thought-out post. Or maybe just group them together and see what happens…

Q: Why is there still a space programme?

One might wonder why nations invest so much time, resources and money into developing a space program.

One might not. One might be more like Brian Cox (the astrophysicist, not the actor/Rector of the University of Dundee) and explain how evolution has led us, humans, to explore the universe. Whether that expansion of the anthropic principle, in a certain sense, is something you agree with or not, he raises another point in his book Human Universe. He probably raises the same point in the TV series that it was based on, but I haven’t seen that. The point is that, thanks to the space-program related research and developments, new technologies have become possible. Directly or indirectly, thanks to NASA (just to give one example), we have:

- LEDs – used for space shuttle plant growth experiments, now absolutely omnipresent.

- Artificial limbs – robot arms to cyborg arms, not that much of a leap.

- A lot of improvements in using solar energy (where do you find huge solar panels? in space!), water purification (no natural sources up there) and waste handling.

- GPS, satellite images of earth (useful for weather forecasting) and other things that require something orbiting the earth.

- New materials

- Modelling Software – whether it’s predicting orbits or the stresses on a rocket during launched, be sure it has been simulated in one way or another.

- Okay, stop the NASA-loving already and answer the question!

A: Why not?

A: (the better one) – Because it feeds innovation; it thrives on the immense curiosity and need for exploration us humans have to push forward technology that not only helps in the actual space exploration, but in everyday life.

Q: But we have all these fancy robotics and whatnot, why would we continue to send people into space?

To answer that, I’d like to quote something I read while I was visiting a friend. When he was asleep, I raided his book closet and ended up reading about 30 pages in an immensely interesting book. It had – amongst a whole lot of other things that I never got the chance to explore further – the following to say:

Despite the immense hazard and cost of manned space flight, most plans for planetary exploration still envision blasting people into the solar system. Partly it’s because of the drama following an intrepid astronaut in exploring strange new worlds rather than a silicon chip, but mainly it’s because no foreseeable robot can match an ordinary person’s ability to recognise unexpected objects and situations, decide what to do about them, and manipulate things in unanticipated ways, all while exchanging information’s with humans back home.

The stuff of thought – Stephen Pinker

A: Because while there are many things that robotics can do, there are some things we are still better at.

*note to future robot overlords: I mean no disrespect to your ancestors in any way, this is a reflection of our inability – at this time – to make you as awesome as you could be. You obviously have surpassed us in any way and I am more than confident that you can succeed in space exploration better than we ever have. But I still dream of going to space, so this helps to make my point at this present point of time. Please do not hold this against me or any future humans.

Q: What are our chances of finding or communicating with aliens?

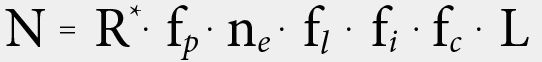

In our own solar system, I highly doubt it. In our galaxy or universe, to be honest, I doubt that as well. I do believe that there is life out there. And there might be proof of this life somewhere at a distance where we can still find it. But unless we find a way to preform hyperjumps or travel through time, chances of communications are very, very, very, very, very, (…), very slim. Someone has done the math. It was to calculate N, the number of civilisations in the Milky Way with whom some form of communications might be possible, or who have the means to emit electromagnetic signals. But it is easily to extrapolate to our (known) universe. This is it :

The explanation of each of these terms is very nicely explained here and in aforementioned Brian Cox book if you prefer paper reading. But just to give an idea of what the stakes are…

First of all, it all depends on the number of planets that bear life. I would guess this number is quite high, there are so many stars in the universe, considering there are an estimated 100 billion stars in the Milky Way alone (though the real answer is: “Uuuh, I really don’t know”) and an estimated 100 billion galaxies in the observable universe. Sure, these stars have to have a planetary system, and some of those planets will have to have suitable conditions for life (but we can send a little girl with blond curls to go test that ), and then life actually has to appear. Those are all statistically very rare events, but if you have a one-in-a-trillionth* event over ten-million-billion-trillion* sample size, that still leaves an astronomical number of events that can possibly occur. I’ll leave you to the math.

* completely random numbers produced by typing -illions

So, occurrences of life might be quite high. But the astronomical distances (“astronomical” is used here, again, in the sense of “huge” or “vast”, in case you got confused) pose a problem. Even if life is out there somewhere right at this moment, and they have the intelligence and technology for interstellar communication, by the time any communication signal will reach them, they could be extinct. Or they would send a signal back and we wouldn’t get it until after our sun has already exploded. Simultaneous means nothing when the distances are so, I’ll use it again, astronomical.

What’s the point then? Well, we could find proof of intelligent life perhaps. We can travel (or send our robot overlords) to distant planets that have the right conditions of life, and see if these conditions have ever sustained life, or if they have the possibility to do sometime. And, we can hope that perhaps, maybe, ten million light years from us, an amazing civilisation sent out a signal 10 million years ago. And that we would be able to detect it. We won’t be able to communicate, but it might be enough just to know that we’re not alone (or have proof, at the least).

A: Finding, perhaps. Communicating, I wouldn’t count on it.

Q: But then why…

A: You know what, you cares? It’s space. SPACE. It doesn’t need an explanation, it needs exploring.

It might have become clear that I have a slight fascination with outer space. Not to say that I am utterly obsessed. One might say I am ‘astronuts’. Completely Bonkers for space. But who can blame me?