In the last few months, a lot of us have been confined to our homes. We no longer commute daily to our workplace, spend less time stuck in traffic, and have canceled our travel plans. With fewer cars on the road, airplanes in the sky, and shut down of some industrial activities, global CO2-emissions are likely to have decreased. In fact, a recent paper has estimated the emission reductions based on predictive models and reported on a daily globar CO2-emissions decrease by ~17% by April 2020 compared with mean 2019 levels.

The same paper predicts that the total average emission of 2020 will decrease somewhere between 4% and 7% compared to the 2019 average depending on the duration of confinement.

It is agreed upon by most of the scientific community, that changes in the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere have an effect on global temperature, this fact will likely not surprise you. But perhaps it will surprise you that this has been known for a long time.

Not just for a few decades. But for two centuries.*

Climate science in the 19th century, yes, it was a thing.

In the early 19th century, scientists had a suspicion that the earth’s atmosphere had the ability to keep the planet warm by transmitting visible light but absorbing infrared light (or heat), and that human activity could change the atmosphere’s temperature, including Joseph Fourier, who mentioned “the progress of human societies” having the potential to – in the course of many centuries – change the “average degree of heat” in an 1827 paper.

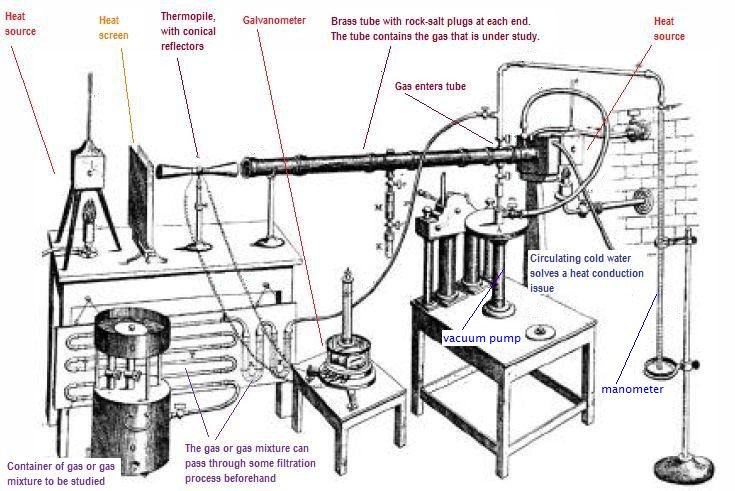

In 1859, Fourier’s theoretical musings were turned into experiments, when John Tyndall, an Irish physicist, published his study investigating the absorption of infrared in different gases. This was the first** experiment showing how heat absorption by the atmosphere could lead to temperature rises, and that certain gasses absorb more heat than others, such as water vapor, methane, and CO2.

Three years earlier…

But wait! Three years before Tyndall’s paper, another paper had appeared in the American Journal for Science and Arts: Circumstances affecting the Heat of the Sun’s Rays, showing how the sun’s rays interacted with different gases, concluding that CO2 trapped the most heat compared to air and hydrogen. The paper was by a woman named Eunice Newton Foote.***

Now, years after her experiments and findings, Foote is credited to be the first scientist to have experimented on the warming effect of the sun’s light on the earth’s atmosphere and the first to theorize that changing levels of CO2 would change the global temperature. In her paper, she stated that:

“An atmosphere of that gas would give to our earth a high temperature; and if, as some suppose, at one period of its history, the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature from its own action, as well as from increased weight, must have necessarily resulted.”

Foote (1819-1888) was a farmer’s daughter and lived in a time where women were typically not considered scientists. She did not have a sophisticated laboratory, so her experimental setup was rather amateurish compared to Tyndall’s a few years later. When her results were presented at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference, it was not by her, but by Professor Joseph Henry of the Smithsonian.

While she gained some recognition for her work at the time, it was rather limited and forgotten by history. Henry presented her work at the conference, prefacing the talk with: “Science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.” and she was praised in September 1856 issue of Scientific American titled “Scientific Ladies.”

It wasn’t until 2010, however, when her paper was rediscovered by a retired petroleum geologist, that her name was slowly put back on the climate science map.

Three strikes, and you’re out!

According to John Perlin, who wrote a book about Foote:

“She had three strikes against her. She was female. She was an amateur. And she was an American.”

There weren’t very many female scientists at the time. Women had a hard time getting formal (science) education.

She did not have a traditional science education and her experimental setup was nowhere near the sophistication of Tyndall’s. her experiment was a lot more simple than Tyndall’s and was limited in its results: she was not able to distinguish between visible and infrared radiation. But her serendipitous discovery that CO2 traps more heat than the other gases she tested, and her hypothesis about changing atmospheric CO2 affecting global temperature, were the first of their kind.

Finally, Europe was still the epicenter of scientific discovery at the time. The US, and physics in the US, was still very much up and coming. At the same time, communicating discoveries overseas without glass fibers and internet was just not as trivial as it is today.

For many decades, John Tyndall was considered the father of climate science, and granted, he was the first to show that certain gases absorbed more heat radiation (rather than radiation in general) than other gases. But Foote was the mother, first theorizing what we now know to be true: changing levels of atmospheric CO2 result in changes in global temperature. And now, almost two centuries later, she’s remembered for it.

So while you’re working from home and putting less CO2 in the atmosphere as a result, spare a little thought for woman scientist who first linked CO2 with temperature. And that the fact that she did, is pretty amazing.

I highly recommend this Cogito video on the history of Climate Change:

* ± a decade or two. But who’s counting?

** spoiler: it was not.

*** This Foote-note is just for the pun.