Hi hipsters.

I’m currently in a room with probably about 250 records. None of them are actually mine (except perhaps this one), but the presence of this amount of vinyl has got me on several thought-trains; remembering when I was back home with my parents going through their 70s and 80s music collection while writing my thesis, or when I was basically doing the Pomodoro technique by working on thesis corrections in chunks equal to however long a side of an lp would play; wondering why people are so into vinyl; wondering how sound can possibly make it onto a piece of polymer that can be read out by a needle, and why are some vinyl records black and other super colorful?

What is vinyl? How is vinyl? Why is vinyl?

Okay, I did some digging. Luckily, I possess the ability (and currently, excess of time) to surf the internet and learn things. Through blog posts, very satisfying YouTube videos, and WikiHows, it’s easy to find out how things are made. But let’s dig a bit deeper and look into the production, chemistry and other science around vinyl.

So, go put on your favorite music, on vinyl or otherwise, sit back and read on.

Vinyl: what’s in a name?

Vinyl is a synthetic material containing a specific chemical group (surprisingly named the “vinyl group”) with the chemical formula -CH=CH2:

Vinyl is also the common name used for the polymer Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC). Polymers are long chains of molecules that have a repeating unit. Polymers are resent everywhere in nature (think proteins and DNA) as well as in man-made materials (synthetic rubbers, plastics, …). In the case of PVC, a repeating unit is a vinyl group with chloride tagged on. This plastic is made from ethylene (from crude oil) and chorine (derived from salt) and looks like a long repeating chain of:

For vinyl making, PVC arrives in pellets that can be melted together and molded into a putty (apparently called a “biscuit”). This is pressed between two plates that contain the negative pattern of the grooves containing the music. Wait… let’s start from the beginning…

The making of a record: Cut, Plate, Press

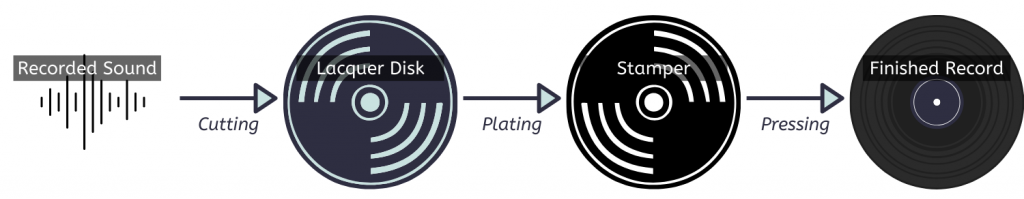

Vinyl records are made through the process of cutting, plating, and pressing.

In the first step, recorded sound is etched onto what is called a lacquer disc, which is a flat aluminum disk coated with a layer of nitrocellulose lacquer (basically a layer of nail polish). Recording machines (called lathes) have a very sharp very very sharp heated sapphire tip that will cut grooves into the surface of a blank lacquer disc due to the vibrations of the recording. This lacquer disc can theoretically be played back (which is also done for quality checking), but the material is too delicate for repeat plays.

It is ideal, however, to create a stamper, the mold used to make vinyl records. To make a stamper, the lacquer disk is first coated with a silver solution. Then, this shiny disk is immersed in a tin or nickel chloride bath for electroplating: tin or nickel particles in the solution are attracted to the silver particles coating the lacquer disk and form a metal layer. This layer will have the opposite structure compared to the lacquer disk: instead of grooves, the physical representation of the sound will be protruding out.

The stamper is then used to press a bit of vinyl putty into a finished record. The two stamper sides (one for A and one for B) are heated to ~ 180°C (~ 350F). The malleable PVC biscuit is placed between the stampers, which are then pushed together by hydraulic pressure – imprinting grooves onto the PVC. Excess PVC spilling over the edges is cut off, et voila, the record is ready to play. This pressing process takes less than 30 seconds and thus the same mold can be reused to make a whole pile of vinyl records with the same music!

You can read in more detail about the vinyl record production process on the internet, for example on How Are Vinyl Records Made? or How Are Vinyl Records Made? (Step-by-Step Guide).

Wait, what about colored vinyl?

PVC is colorless in it’s raw form, so to create that typically black record look, PVC pellets are colored using carbon black. This is the same material that makes car tires black. In cars, it has the excellent properties of being conductive – making sure there’s no static electricity building up in your tires – and of making rubber sturdy. In vinyl, it also reinforces the polymer making the material stronger and more stable over time, ensuring that you can play the record time and time again with the same sound quality (-ish).

Now, PVC pellets can be colored to create different colors using different dyes. Historically, these dyes would not have the same reinforcing effect as carbon black, but nowadays the difference in quality is negligible. In fact, production mistakes have a bigger effect on sound quality and durability than leaving out carbon black.

Not just any color is possible, but some amazing effects can be “melted” into the records, quite reminiscent of glass blowing.

(Soundtrack for the game Hohokum)

Edit on 4/24/2020: This is extremely satisfying and relevant:

Another option is picture disks, which consist of 3 distinct layers: one layer is a clear PVC layer without any music, the second layer has the picture, and the third layer is a clear plastic sheet containing the grooves for the music. This final plastic layer is more malleable than PVC and therefore not as durable; picture records (and glow-in-the-dark records) are more susceptible to loss in durability and sound quality but you’d have to be a real expert to really notice.

(Soundtrack for the game Final Fantasy VII)

Keep on turning

There you go, you have all the information you need to become a vinyl record collector. And impress other record collectors with your knowledge on vinyl. Shall we talk LaTeX next time?

Sources linked throughout the text. Cover image is from Bit.Trip’s “Greatest Chips”