Neat process diagrams of metabolism always gave the impression of some orderly molecular conveyer belt, but the truth was, life was powered by nothing at the deepest level but a sequence of chance collisions. (1)

Zoom down far enough (but not too far – or the Aladdin merchant might complain) and all matter is just a soup of interacting molecules. Chance encounters and interactions, but with a high enough probability to happen. In essence, life is a series of molecular interactions (that, in turn, are atomic interactions and so on and so on…)

The form of the cellular framework of plants and also of animals depends, in its essential features, upon the forces of molecular physics. (2)

Quite often, we can ignore those small-scale phenomena, but only as long as the system we are describing is large enough. As in physics, in biological systems size does matter (*insert ambiguous joke here*). We have to adapt the governing physical rules depending on the scale that we are observing. Do we consider every quantum-biological detail, can we use a cell as the smallest entity or even use whole organisms as the smallest functional entity?

Life has a range of magnitude narrow indeed compared to with which physical science deals; but it is wide enough to include three such discrepant conditions as those in which a man, an insect and a bacillus have their being and play their several roles. Man is ruled by gravitation, and rests on mother earth. A water-beetle finds the surface of a pool a matter of life and death, a perilous entanglement or an indispensable support. In a third world, where the bacillus lives, gravitation is forgotten, and the viscosity of the liquid, the resistance defined by Stoke’s law, the molecular shocks of the Brownian movement, doubtless also the electric charges of the ionised medium, make up the physical environment and have their potent and immediate influence on the organism. (3)

Observing life at the smallest scales (by which I mean cells and unicellular organisms) at least has the advantage the rules driving form and structure can, at least in many cases, be considered relatively simple: surface-tension.

In either case, we shall find a great tendency in small organisms to assume either the spherical form or other simple forms related to ordinary inanimate surface-tension phenomena, which forms do not recur in the external morphology of large animals. (4)

While on the topic of size, as many things in the universe: size is relative. I have noticed in conversations with colleagues and supervisors that what is considered small or large, definitely depends on the point of perspective (and often: whatever the size is that that person typically studies). I could assume that for a zoologist, a mouse is a small animal, but tell a microscopist they have to image an area of 1 mm² and the task seems monstrous. For a particle physicist, a micrometre is immense, but for an astrophysicist, the sun is actually quite close.

We are accustomed to think of magnitude as a purely relative matter. We call a thing big or little with reference with what it is wont to be, as when we speak of a small elephant of a large rat; and we are apt accordingly to suppose that size makes no other or more essential difference. (5)

Undoubtedly philosophers are in the right when they tell us that nothing is great and little otherwise than by comparison. (6)

There is no absolute scale of size in the Universe, for it is boundless towards the great and also boundless towards the small. (5)

That’s the amazing thing about science: we strive to understand the universe on all scales. The universe is mindblowing in its size, in both directions on the length scale.

We distinguish, and can never help distinguishing, between the things which are at our own scale and order, to which our minds are accustomed and our senses attuned, and those remote phenomena which ordinary standards fail to measure, in regions where there is no habitable city for the mind of man. (7)

Good thing we have scientists, amazing minds, capable of studying, visualising and even starting to understand the universe on all its scales…

(1) Permutation city – Greg Egan, p. 67

(2) Wildeman

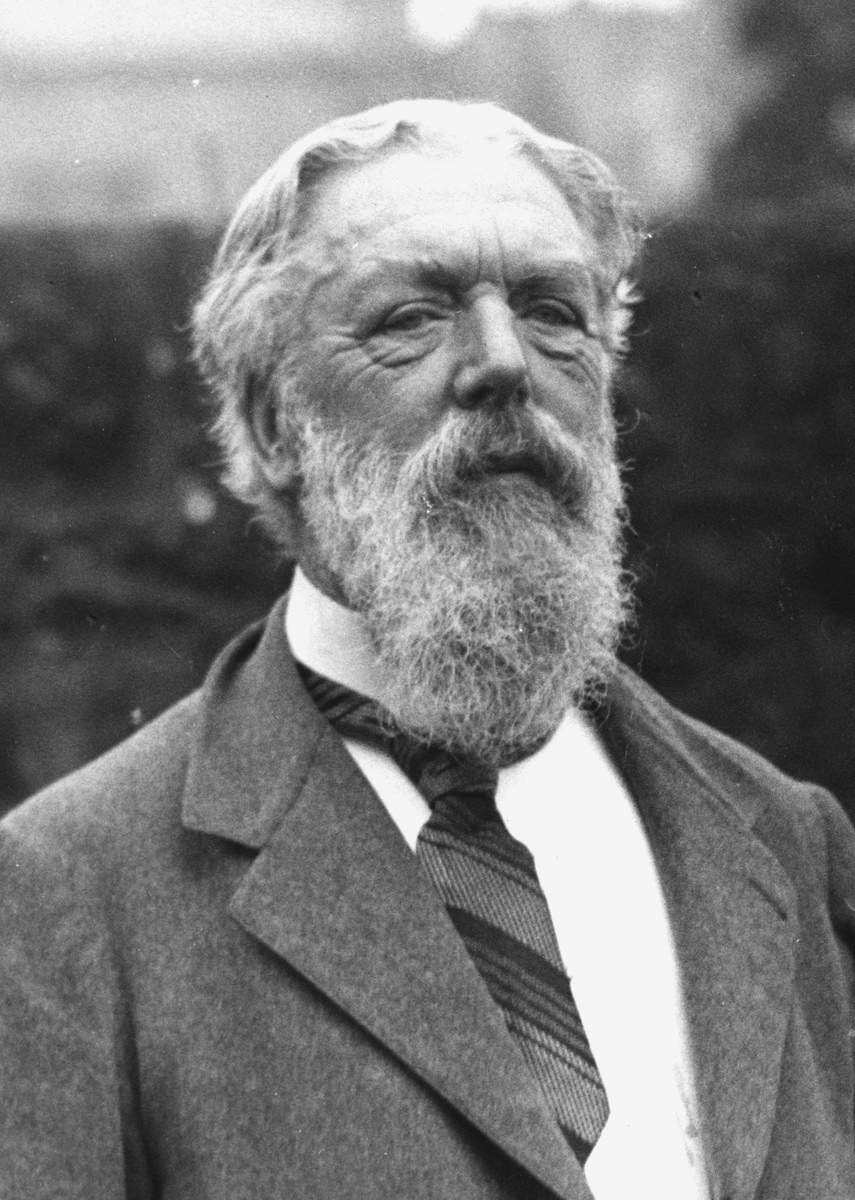

(3) On Growth and Form – p. 77

(4) On Growth and Form – p. 57

(5) Gulliver

(6) On Growth and Form – p. 24

(7) On Growth and Form – p. 21

(3-4, 6-7) from D’Arcy Thompson, On Growth and Form, Cambridge university press, 1992 (unaltered from 1942 edition)

One Reply to “When size matters (100 years, Part VI)”